Story courtesy Nick Cotsonika, NHL.com

LAS VEGAS — Darcy Haugan set an example to the day he died.

The coach of the Humboldt Broncos, a team in the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League, received a text message from his wife, Christina, on April 6.

She was the team office manager and gathering what she needed to make pasta meals for the bus trip that afternoon. The Broncos were to play at Nipawin that night, trailing 3-1 in a best-of-7 playoff series.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” she told him. “It’s a game day. I shouldn’t be texting you this and stressing you out.”

“You guys are always more important to me than a game day,” he responded.

Darcy was one of 16 people killed when the bus crashed on the way to the game. He will be remembered as more than a hockey coach. He used the sport to make players better people and the world a better place.

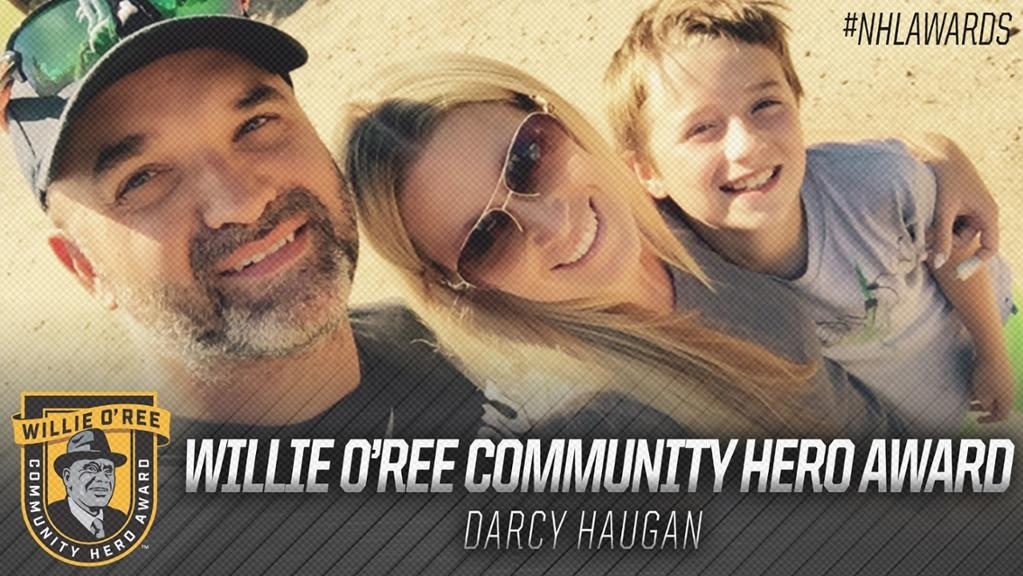

At the 2018 NHL Awards presented by Hulu at the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Las Vegas on Wednesday, backed by 10 surviving members of the Broncos, Christina accepted the inaugural Willie O’Ree Community Hero Award on Darcy’s behalf.

O’Ree, the first black player in the NHL, has been the League’s diversity ambassador for more than two decades, using hockey to build character and teach life skills. The award goes “to an individual who — through the game of hockey — has positively impacted his or her community, culture or society.”

Fans submitted candidates. O’Ree selected three finalists in consultation with the NHL. Fans voted for the winner.

“Darcy would always say, ‘Family first and then hockey second,’ ” Broncos forward Kaleb Dahlgren said. “Some coaches are just X’s and O’s and strictly hockey. He taught us a lot of valuable lessons in life as well as on the ice, which really speaks to his character.”

Christina Haugan, wife of Humboldt Broncos coach Darcy Haugan, winner of the Willie O’Ree Hero Community Award.

Darcy kept a Bible on his desk, started each day by doing his devotions to ground his life and never missed church, even if the team had returned from Flin Flon at 4 a.m., because he wanted to instill into his sons — Carson, 13, and Jackson, 9 — that it was important.

When he coached for 12 years in his hometown of Peace River, Alberta, he’d spend lunch breaks on a floor hockey program at Springfield Elementary School, teaching students and making sure his players who were supposed to be there showed up.

As soon as he arrived in Humboldt three years ago, he and his new players played street hockey with kids at a festival. Soon they were reading to kids in schools. Someone sent Christina a photo Tuesday. It was of Darcy standing in front of a classroom full of kids, a selfie and yet …

“He was selfless,” Christina said. “He always thought of everyone before himself.”

One day in February, Humboldt was hammered by a heavy, unexpected snowfall. The Broncos needed to practice with the playoffs approaching. Didn’t matter.

“He’s like, ‘You know what? We’re going to cancel practice today, and we’re going to go shovel snow,’ ” Dahlgren said. “And we’re like, ‘What? Like, what do you mean?’ And he’s like, ‘Nope. Community service. We need to do it. We’re Broncos, and we’ve got to do it for our community, because they’ve supported us this whole way.’ And so we all got our shovels and got shoveling.”

First they did the pathways around the arena to help the staff. Then they went home and helped their billet families. Then they tweeted an offer to anyone else who needed help, and the calls came ringing like crazy. They cleared driveways, dug cars out of ditches, worked from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. or so.

“It was great to give back,” Dahlgren said. “And he always wanted us to give back in any way possible and be a part of the community of Humboldt.”

Darcy was developing a program he wanted to call “Haugie’s Heroes.” He was going to donate money to charity partners for each goal the Broncos scored, hoping to inspire businesses to get involved. The National Hockey League Foundation will donate $10,000 to a charity that was important to him: the Saskatchewan Brain Injury Association.

After he died, Christina heard stories she never had before — so many that the players are collecting them in a book for her. Darcy helped players with personal problems and gave them second chances, even when maybe they didn’t deserve them. His office was always open.

“He cared very much what they did on the ice too and wanted to win, but he always said that he cared more about that they were better people when they left the organization,” Christina said. “He didn’t need any credit. He didn’t need anybody to know no matter what he’d done. It was about the person. He just wanted to help them.”

Darcy used to say, “Take care of the seconds, and the minutes take care of themselves.” He’d end pregame speeches by saying, “It’s a great day to be a Bronco, gentlemen.” At least one surviving player, defenseman Bryce Fiske, has gotten a tattoo of those words.

“Which just summed [Darcy] up so much,” Christina said. “He was just so proud to be a coach, and he wanted them to be equally proud to be a player. He was always telling them, ‘You guys are so lucky to be able to do this. Like, you guys are playing hockey full time essentially, right? Just cherish every moment of this, because it won’t last forever.'”

The Broncos will be a family forever, and it’s family first and then hockey second, right?

Surviving players have followed Darcy’s example. They have come to the Haugans’ house to play video games with the sons and take them for ice cream. They have shown up for the sons’ soccer games. They have sensed when Christina has had a hard time.

She had an emotional moment on the plane to Las Vegas. Instantly players were there, holding her hand, supporting her. Center Brayden Camrud told her he would visit her in an old folks home. She laughed, thanked him and reminded him she wasn’t that old.

“They know how much he loved them,” Christina said. “I told one of them yesterday. I said, like, ‘If he had had the option in the accident to protect one of them and knowing that he was going to [die], he would have done it in a second, because they meant everything to him.’ …

“He did want to make a difference. I don’t think he ever expected any credit or ever thought he ever would be recognized like this. So it means a lot. I wish that he’d known a little bit, you know, the impact that he did have.”